something that’s been on my mind lately is the practical side of hobbyist and student woodworking. i have the advantage of a significant amount of shop-time in a typical week. while i don’t spend as much time as i’d like building furniture, i do spend a lot of time designing and teaching about it and that is a luxury many hobbyists and students i encounter simply don’t have. the other thing is that i don’t have to think nearly as much about the cost of materials because my reason for doing this is mostly educational rather than production — i’m not building furniture for my house and the initial outlay is usually going to be covered either by revenue from teaching about that particular project later or writing about it in a magazine or whatever. while that’s not generally explicit (selling a project with $500 of lumber for $2500 and it being definitely worth the investment), the fact that i have to build a piece a few times before i can teach it in class comes with the territory and there’s just no way i’m worth my teaching fees if i haven’t at least gone through the entire project we’re making in advance to make sure there are no possible problems — usually at least a few times, honestly, as there are always issues the first time building anything, as i’m sure any woodworker has discovered.

this is, of course, the reason i always encourage people to prototype everything using cheap materials regardless of the desired outcome. even if you’re only planning to ever build one, you want the one you build to be the best-possible version you can make and that’s never going to be the first attempt. building a workbench? plan on making a second one. soon. making a dining-table? make sure you do a mockup in construction lumber because something will definitely go wrong and you don’t want to spend hundreds on some beautiful cherry or walnut and have to start looking for stop-gaps or change the dimensions of your table because you’d just cut a piece the wrong size or at the wrong stage of the process.

but one of the things i’ve talked about in passing though rarely spent a lot of time discussing is probably the most important part of the whole process. there are several stages in the design process the way i do it.

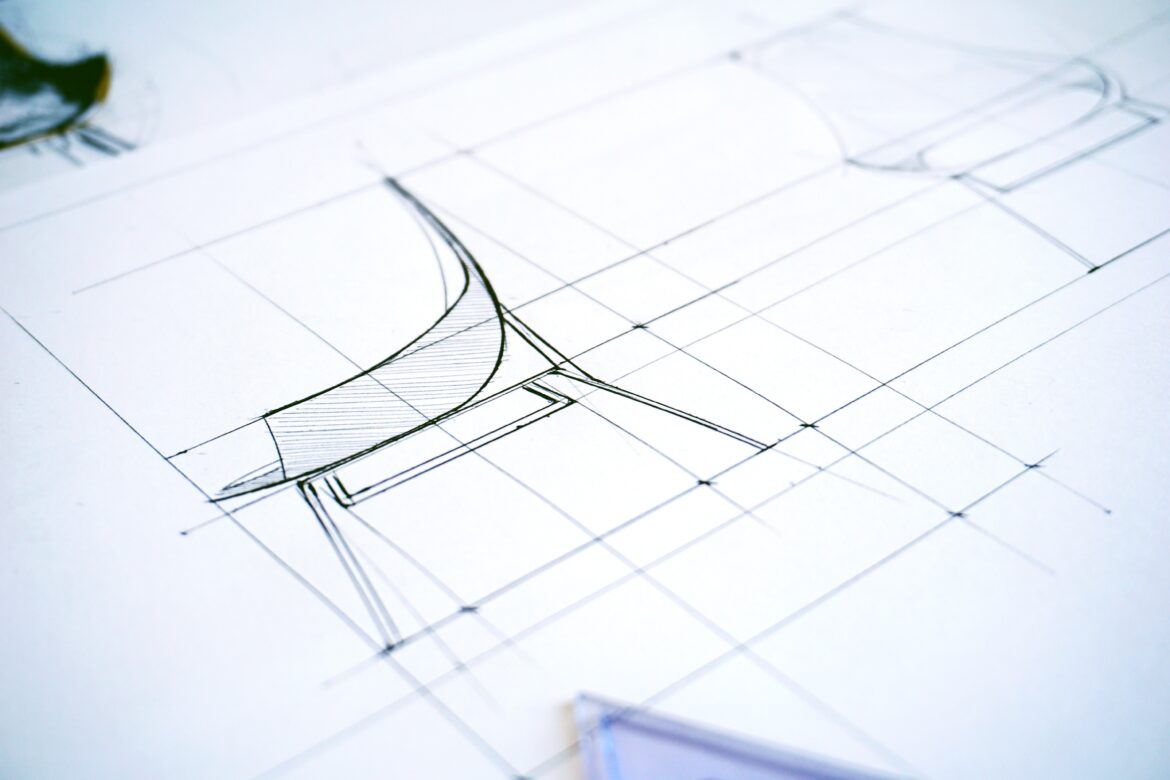

- first i get a vague idea of the shape of a piece. i do this on sketch-paper, drawing curves and angles and forms in a loose, fast style to get the motifs i want to include on paper. is it going to be japanese-style? korean? mission? arts-and-crafts? they all have signature aesthetic details.

- second, i start trying to get the lines. once i have the things in my head on paper in a quick sketch (or a hundred), i can start to refine. i’m not worried about scale at this point. how thick the pieces are doesn’t matter. i’m treating the whole thing as a dimensional shape. so the piece tends to look a little spindly but i’m trying to get the outside shape. you can think of this as the “block-size” — in other words, if i was going to wrap the piece and stick it under the christmas tree, what would it look like as a silhouette?

- third, with the lines in place, i start to worry about specifics like angles. particularly angles, actually. dimensions can come a bit later but things like rake and splay of legs, taper angles, etc. these define the aesthetic of the piece a lot more than the size — having a ten-degree taper on a leg changes a huge amount about its look but whether it’s 500mm tall or 600mm tall is a much more subtle thing. of course, some of these dimensions are built-in and have to be there if the piece is fitting in a space. you know your bookcase is going to be about 1800mm tall. you know your chair is going to be about 460mm to the top of the seat. because they have to exist in the real-world. and that’s a good way to start — fill in all the necessary dimensions then worry about the proportion of the secondary ones. but first i try to get all the angles right in my head.

- fourth, i get all the dimensions solidified — once i have the necessary ones in place, i move to the secondary ones then, finally, to the thicknesses and depths — for example, i start with the height and width of a desk then worry about its depth then about the thickness of the components and, finally, about its drawer-components and things like runners and internal dividers. start with what you see that changes how a piece feels then move to the things you see that have less impact then to the things you don’t really see or notice.

- fifth, i try it out in-real-life. this is what we’re going to talk about today.

- sixth, of course, i build it, starting with a prototype or two to make sure it’s what i want then moving to a final-ish piece, perhaps making one or maybe moving on to making many, especially after i’ve gotten the prototype solidified and any problems solved so i can batch-create a dozen or more of them in a classroom setting. or maybe just one for a friend who needed it in the first place.

see what i mean about glossing-over the trying-it-out-in-real-life step? this is what happens every time i talk about the process. and, because there’s so little said about it, people tend to skip it. like it’s not important. well, today i’m telling you i think it’s not just a significant step but perhaps the most important one other than the final build. this is how i suggest you do it. it’s my process and it works for me and most of the people i’ve encouraged to try it — ok, forced to try it. it’s what i use in-class as a pre-prototyping method. but i have found that students who use it in-class find it both effective and efficient and use it when they are no longer being graded on their work.

what is this process? well, i should probably first mention this isn’t “my process” in the ownership sense. i didn’t create this process and i would be an idiot to take credit for something that’s been common in the artistic world for centuries — it’s hard to be the inventor of something that’s existed since before your grandparents were born! but it’s actually surprisingly-rare in woodworking. i’ve definitely seen a few well-known woodworkers use something similar but not many. if you’re curious and want to look at some other examples of it in the wild, you’ll find articles in various magazines (fine woodworking, popular woodworking, etc) by michael pekovich and tom mclaughlin about their design procedures. by the way, they both have extremely different processes from me in practice but i mention them not because we design similarly (though i’m told my designs are similar to sir pekovich’) but that this particular step is a large portion of their process. i do almost my entire process in 3d-modeling software (fusion 360 or shapr3d — usually the first for many reasons i will discuss in another article — but never — and i repeat never — sketchup, as it’s a massive waste of time and effort) while mclaughlin does the whole process on paper and pekovich is more old-school and does most computer-modeling in 2d using design software, instead. i guess i’m a child of my generation, after all — i remember checking out library books on cad/cam when i was a preteen and the local library was bringing them in from the university because nobody but engineering students and me were interested.

so let’s talk about it. full-size drawings and 3d-in-real-life placement. first we’ll look at how to do it then talk a bit about why you should — and why you shouldn’t see this as an extra step to be eliminated as you get better at woodworking, much more a vital component even in an expert’s arsenal of tools.

to talk about the how, i need to take you through my design process. i think this is the process you should be following. you don’t have to. but it simplifies things in your whole creative life and the cost is extremely low — usually the cost of a few sheets of paper and some tape. it requires no rulers, complex measuring devices, specialized drafting or drawing or sketching equipment or any artistic talent — which is, by the way, just a proxy for “experience”. if you want to learn how to draw, you need to spend thousands of hours practicing drawing. i draw adequately. which is quite an admission for someone who teaches design and, for a few years, fine-art at the college level — in my defense, i was mostly teaching photography and media studies, areas i truly am experienced in doing in industry. but being seen as a talented artist by the students always felt like a bit of an act, especially when i was asked to fill-in for others in the department to coach their sketching and painting classes when sudden illnesses occurred. i know the theory. but i haven’t put in the hours of practice. i got through it, though. and i do love drawing, just not enough to spend thousands of hours on it.

so this is what i do. no drawing talent required.

every design process starts with inspiration. i look at hundreds, thousands, sometimes tens-of-thousands of photographs for inspiration. sometimes i look at things in the desired style. more often, i look at things in the desired form — if i’m building a dining-table, i look at thousands of pictures of tables from all schools of design before even thinking about refining my style because so many things are common — proportion, dimension, structure, etc. i want to get those all firmly-grounded in my head before i get specific.

something i should mention here is that i’ve designed and built a lot of things. a lot. this isn’t a “beginner thing”, looking at many examples. i think it’s possibly even more important for someone experienced who might have gotten stuck in habits of thinking “this is how you build a table” or “this is my personal style”. there are always many ways and your style is never fixed in a single place until you’re dead. you should always be growing, adapting and developing. so you should be looking. not looking at photographs of beautiful furniture for inspiration would be like a writer saying they’re never reading another novel because they don’t need to see how others write or a painter simply avoiding all art galleries for the rest of their life.

once i have the inspiration, i take all the little notes i made — i always make notes when i look at things, by the way, though perhaps your memory is better than mine and i suspect, after all the medication i’ve been forced to take in my life, it probably is. my students generally tell me they look at photographs and start sketching once they have a more solid idea. master-craftspeople i know say much the same thing. i start sketching while i’m looking at the inspiration images. take your pick. either is totally fine. so i take those notes and sketch a vague design. then i sketch another. and another. when i have maybe ten or twenty rough designs, i take them all and stick them to the wall with tape. or pins. where i am now there’s no corkboard so i just use tape. i stare at them for a few minutes or while i do something else that doesn’t require much attention and try to see what i like and don’t like about them.

with that in mind, i try to draw a realistic shape of the piece. it doesn’t have to be perfect and it’s not going to be the final outline in any sense. but i try to get the thing done. front-view, side-view, top, bottom, whatever i need to remind myself what i want it to look and feel and function like — which way do the drawers go? how are the shelves divided? i make notes on the paper like “this shelf is the only one for tall books” or “i need three tiny drawers up here for different types of paper”. with that done, i put the paper and pencil away.

i always get asked, by the way, what i sketch on and with what. i don’t think this really matters nearly as much as people seem to give it credit for but here’s my answer. i use a kuru toga mechanical pencil — it’s awesome because it rotates the graphite to make sure it’s always sharp and never gets a weird angle when you’re drawing, making your lines more accurate — at .5mm. and i draw on watercolor paper or, if i’m just rough-sketching and don’t care too much, basic copy-paper. i know a lot of people like to sketch with fancy pens in expensive pads but here’s my simple way to look at it — i want a pad that’s about letter-size, no more than about a hundred pages or it’s too think and coil-bound so it doesn’t keep closing and i can flip the whole thing open to a single page. i don’t want anything getting in the way — i’m not a great artist so i’ll take all the lack-of-distraction i can get. you can use what i use or you can use something else. the important part is to get paper that’s big enough (don’t use a tiny pad), plain enough (no lines, for fuck’s sake) and won’t get in the way (coil-bound is nice but you can get anything that sits flat) and a mechanical pencil you like the feel of in your hand — if you’re ok with the plastic bics, that’s totally fine. i think the aluminum is much more comfortable and a better size that’s easier for me to hold and i’ve had the same two pencils for years so the twenty-dollar investment was well-worth-it.

then i load fusion 360. no. i don’t go through an intermediary stage of designing in something simpler like sketchup (which is awful) or shapr3d (unless i’m not at my laptop) or illustrator (as much as i love illustrator — it really is the best design software ever made and i use it nearly every day — it’s not nearly as useful for 3d work and it requires far too much imagination and mental energy, though it can definitely be done, as is seen in pekovich’ designs and sometimes i use it for things like kumiko patterns where 2d faces are so important and the depth is an afterthought). i start designing right there on the blank screen.

first i take the things from my sketches and put them in. then i start constraining them with actual measurements. then i move them around until they feel right. i talked about this multistage process already, starting with outlines and shapes, gradually progressing to more and more secondary measurements and specifics. i’ve talked about this process in quite a bit of detail before but i suspect i may have to make some videos about it to really show people the process in-depth. i think you probably get the idea, though.

at this point, though i have no affiliation, i should probably mention a series of videos. there are many paid courses in how to use fusion 360 for design, often specifically for woodworking design. they might be relatively good courses but i promise you can save your money. there are two things you should watch if you want to learn to use fusion 360 and they’ll get you so far down that road you’ll find the paid ones are simply telling you things you already know. the first is a relatively-recent video i was very impressed with by foureyes furniture detailing their process for design in fusion 360. this gives you a great basic introduction to how it can be useful in your workflow. but if you really want to learn how to use it, watch the introductory videos by lars christiansen and — and here’s the really important part — watch as many of his livestreams and instructional videos about more advanced skills as you can find time for. they’re not about woodworking. but they’re incredibly-useful and i use those skills every day. i encourage my students to watch them all — he’s engineered the videos mostly for beginners and you can use the program and follow his steps as he does them. anyway, i’ve never done video tutorials for fusion 360 and i don’t really have any plans to in the near future. but i’ve taught it quite a bit — there’s no need for more instructional content about it, honestly, given how thorough christiansen’s channel is and i try to be useful with my information. maybe time to do a few woodworking-specific things like working with dimensional stock but that’s an idea for another day.

i will assume you know how to use the software and have built a reasonable 3d model of your project. don’t worry about getting it perfect. the idea is to get the approximate shape. don’t forget to make it look like wood. it doesn’t have to look like the actual wood you’re going to use — i almost always tell it to look like oak because the oak texture is fairly nice in color and easy to see on-screen, regardless of what i’m actually building from, which is almost never oak — maple and cherry, occasionally walnut. the issue here is to make sure you have a vague idea in your head and sometimes those metallic-looking hard shapes just don’t do it but your head will make the leap from fake-onscreen-wood to real-life-wood much more easily than plastic-to-tree-parts.

with that done, print your model. life-size. seriously. export the whole thing as a pdf (there’s another way to do this and i’ll get to that in a second) and print it. if you use adobe’s reader, which i suggest using, you can use its “poster-mode”, allowing you to print on multiple sheets of paper with guide-line so you can fold and tape them together to get an actual-size representation of the parts. what’s the other way? take measurements, get a huge sheet of paper, draw by hand and wonder why you didn’t just print the thing from a pdf. you only need to do this for the front-view, really. though you may want to repeat this technique for the side-view on some projects if you are wondering about it later in the process.

some people will tell you, at this stage, to stick it to the wall where you are thinking of at-least-temporarily staging the piece or, if it’s something more permanent, where it will live. and i advocate this process if you don’t have the willingness to go a little deeper but i think you should. get a cardboard box. tape the design to the front of the box so it hides the box but the box keeps it flat. trim the box so you don’t see any of it sticking out from behind the printed design. now check the depth of the piece and use the box to position the thing so the front-face of your piece is as far from the wall as it’s intended to be. your design at this point might be just lines or it could be a color/black-and-white textured print. either works. but now you have a representation not only of what it will look like in the space but its physical presence.

go to the other side of the room and sit — i sit on the floor but you can use a chair if you prefer. look at it. then do something else. look back at it from time to time. perhaps do this over a period of days. keep notes. what do you like? what don’t you like? does it look too big or small? are there parts that don’t seem to fit? are the curves too subtle? too aggressive? what about the thicknesses of the parts? do they look too bulky or maybe, though i’ve never made this mistake on designs and tend to always design too-fat components at first, too thin and spindly? keep going until you stop thinking of things you’d like to change. then go back to your model and change them.

repeat the process.

do this until you’ve got one you’re happy with. then move on. this will save you untold hours of building and literally thousands of dollars of material costs, not to mention the self-loathing that comes with building a piece only to realize the sides are so over-thick it looks like your chair was meant to be a prop in a hippopotamus park.

i know it’s nothing revolutionary from a conceptual standpoint. but offset-fullsize-prints as a design tool is probably the single most significant thing in my whole experience of designing and building that has taken my furniture to the next level. if you want to design better, it might not actually have anything to do with having better ideas, more talent or more time to spend on designing at all. it may just be that you haven’t made enough mistakes before building the piece. make the mistakes on paper. paper’s cheap. wood’s not.

i hope that’s useful and gives you something to contemplate when you’re getting ready to do your next project. may the spirits of the trees keep you safe and smiling today. thanks for reading!