there are three awesome basic guides necessary for handtool woodworking. the best saw guide you’ll ever use is a flat piece of plastic with a couple of magnets in it. the best chisel guide you’ll ever use is a … flat piece of plastic with a couple of magnets in it. the best shooting board, however? that’s a little more involved. let’s talk about it — why you need one, what planes work best, what to build it from, how to build it and possible adaptations for advanced (supplementary) shooting boards. this one won’t do ten magic things and cut your lawn. i’d much rather have several simple ones than one with bells, whistles, antlers and shiny dentalwork. you can build a frankenstein-type monstrosity. but don’t. just … don’t.

by the way, i have been told sometimes the plan diagrams and images don’t show up on everyone’s browser. i suspect this is because they are fairly large and get detected as ads. i can’t really fix that because they’re large and shaped like … images. if you can’t see them, there are two possible reasons — i write the articles before posting the images so they might not be there yet. or your browser might be cheating you and you should shoot it. with a board. either way, feel free to email me and ask for the diagrams. if i haven’t finished them yet, i’ll send them when they’re done. if i have and you just can’t see them, i’ll send them as soon as i get a chance. if anyone tries to sell you copies of my plans or tells you you have to subscribe somewhere to get them, don’t. and let me know because if anyone’s going to profit from this shit it should be me. and i’m not trying to so nobody else should be, either. i love this craft. it’s already too expensive. i refuse to make it more. people want to give me some money cause what i did helped them? no problem. but i won’t make my assistance dependent on money. money is evil. really. i’m a communist. go figure.

what’s a shooting board? (and while we’re at it what’s shooting?)

the basic answer is it’s a jig or guide that helps you get a perfectly-perpendicular end on a piece of wood. (say that three times fast…) you put a (usually long) piece of wood against the fence of your shooting board and “shoot” it with a plane. the end of the board will be 90-degrees to the faces in both axes (horizontal and vertical) and the board will get shorter by one shaving with each pass. you can quickly and predictably dial in the length and precise angle on the end of the board.

you can also make a shooting board with an angled fence to create non-90-degree angles on the ends of boards. the basic one i discuss here is meant to do 90-degree angles and, with the addition of a speed-square, 45s.

shooting in the context of woodworking simply means using a plane to trim the end of a board precisely. it doesn’t necessarily imply you’re using a guide but if you’re doing this without a guide you’re probably getting hit-or-miss results — sometimes you’ll nail it and other times you won’t. much like with everything else guide-related, the guide doesn’t mean you get a better result. it means you get the same result every time. doing things freehand is unpredictable at best. even the best woodworker in the world fucks up sometimes. and i’m far from the best. i’ll take predictability. perfection is a myth. but repeatability isn’t and a shooting board is a great way to get repeatable cuts. once you make one good cut with it, you know you can duplicate it. so if that first “perfect” cut takes you an hour, the next one will take you thirty seconds and suddenly that hour is an excellent time investment when you have to cut the next thousand pieces.

why do i need a shooting board?

if you’re a woodworker, you probably make furniture. you might make other things but we’ll assume for the moment you make furniture. furniture has joints. those joints are either accurate or they’re not. if you make furniture with inaccurate joints, you haven’t made furniture. you’ve made pieces of wood in the vague approximate shape of furniture that is about to become kindling. accurate joints (also known as joinery — done by a joiner like snug in “a midsummer night’s dream” — yes it’s an old term and no i hate old terms in general but this one is quaint and cute and despite thinking shakespeare is a worthless fool from an age best forgotten he’s a cultural icon and, like most cultural icons, an interesting mental reference for people) are the mark of good woodworking. there are many things necessary for an accurate joint but they almost all have one thing in common, regardless of type — dovetail, mortise-and-tenon, miter, rabbet — two pieces of wood come together and rest against each other with flat surfaces. a shooting board allows you to get predictably-flat surfaces on the ends or edges of boards. get that right every time and you’re well on your way to accurate joinery. fuck it up and you’re well on your way to some very expensive pyrotechnics in the back garden that smell an awful lot like hundreds of dollars of walnut going up in smoke.

need another reason? they’re fun. using a shooting board is one of the most enjoyable things i’ve ever found in handtool woodworking. it’s easy to do yet never seems to feel boring. i might be weird. ok, i’m weird af. but i suspect you’ll feel the same way once you try it.

what do i shoot with?

we’ll get the pointless humor out of the way first. no, you don’t need a double-barreled plane for accurate shooting. it doesn’t take shells. and you won’t get arrested for possession if you own a shooting board. now that our inner teens are satisfied, let’s move on.

you can shoot with any plane. but you shouldn’t.

there are some planes better-suited for the task than others. a big, long plane is not going to work well on a shooting board because you don’t need a shooting board that long. so a 7 is simply overkill. on the other end of the spectrum, a 3 is too small. don’t shoot with a 3 unless you’re making model furniture. if you’re making things in miniature, use a block plane and make a shooting board to fit it. but i’m assuming here you’re making human-sized furniture. anything dramatically larger or smaller and this isn’t the shooting board for you. i think this will cover most of us, though. nothing wrong with baby furniture. just not my thing. i’ll leave it to barbie to build her own coffee-table.

so what we’re talking about is a bench-plane between a 4 and a 6.

there are other options. you can shoot with a block plane but that’s going to be very limiting in terms of the thickness of the wood you’re shooting. let’s think about this. the plane is sitting on its side and rubbing against the end of the piece of wood. that means the maximum thickness of your wood is determined by the width of the blade. the largest block plane blades you’re likely to find are about 41mm. which means you can’t even shoot a 50mm piece of wood. given that a lot of commonly-used pieces are precisely that, 50mm thick, this could be a significant limitation of your shooting board. as a tool, though, a block plane is great for the task. it’s just too small. if you only shoot thin boards, go for it.

while we’re on the subject of block planes, though, which tend to be low-angle and bevel-up, the planes that tend to work best for this are low-angle planes. this is because most of the work done on shooting boards is trimming endgrain. that’s what low-angle planes were designed for. many people swear by these planes — i tend to swear at them. they’re absolutely overrated and if you get better results from your low-angle smoother it’s simply because you didn’t set up your high-angle bevel-down smoother well enough and you should work on your setup game. that’s not to say they won’t get good results. just that they’re not the deified objects people often think they are. they’re easier to setup — no chip-breaker, no complex geometry to wrap your mind around. that doesn’t mean they’re better or the right tool for the job in most cases.

in this case, however, they absolutely are. there are dedicated shooting planes. don’t get one. they’re expensive and expensive and expensive and simply not worth it. unless you have lots of extra money. in which case you can go to down but you don’t need one. not even if you’re a professional or wannabe professional. a standard bench plane or low-angle jack will do just fine — actually, it’ll do better than just fine. you won’t get better results with a shooting plane unless you did a bad job setting up your regular plane. the results will be perfect in both cases. but if you buy a shooting plane those results will have a much larger impact on your pocketbook.

i know what you’re thinking, though. this is an excellent excuse to buy a bevel-up jackplane. and it is. if you wanted an excuse to get one, this is the one you’ve been waiting for. it really does do wonders on a shooting board. there are a few things you should know about them, though. the lower sharpening angle (about 25 degrees instead of the 35 you are probably using on your bevel-down planes) means it will dull dramatically faster. and they are expensive. let’s say that again so it sinks in. they’re really expensive. they’re worth the money (sometimes) but they’re not cheap.

i will tell you a story to illustrate this point clearly and show just how much of a difference there is. there are two ways to buy good planes. you can buy vintage or you can buy brand-new. there are plenty of manufacturers out there that will sell you a beautiful new plane but there are really only three you should be considering if you’re going to buy one — veritas (and if you just end the list here it’ll be ok), wood river and quangsheng. note i didn’t put lie nielsen on this list. don’t buy a lie nielsen plane. they’re not worth the money. they’re well-made but they’re just copies of old stanley planes and other companies (primarily wood river) are making equally-well-made modern copies of those same planes for vastly less money. when lie nielsen comes out with a new-and-improved version of a plane, that’s when it will be worth buying one. until then, they make some other beautiful tools (chisels, for example) that are definitely worth looking at.

while i’m on the subject of lie nielsen and wood river, let’s get something very clear here. there are many companies out there that make copies of old planes. there are many that make modernized adaptations with all kinds of improvements not just in manufacturing quality but design (veritas, for example, and bridge city). these are not the same thing. if you take a bedrock 604, disassemble it, reproduce all the parts and sell that, you’re selling a bedrock 604. this is what lie nielsen is doing. and they’re doing it very well. but a lie nielsen copy of a bedrock 604 sells for about three-hundred bucks. a wood river copy of a bedrock 604 sells for about half that. they’re both copies of a bedrock 604. they’re both extremely precisely-machined. which one is better? they’re pretty much indistinguishable. same materials, same process, same original.

while i’m on the subject of copying old designs, by the way, i’ll make one other point about this. if your business model is duplicating old things and selling them, that can be an excellent way to make money as long as the original designer/manufacturer doesn’t have a problem with it. stanley doesn’t make those bedrock planes anymore and they don’t likely give a rat’s ass if someone else does. but if you then want to complain someone else is making a copy of the thing you copied… there is a word for that. and it’s rather vulgar. don’t do that. i’m not an american, by the way. i don’t care where a tool is made. i care if it’s made well and i care if it’s made ethically — as in, not by slaves or people paid almost like slaves. don’t want to buy an import? you don’t have to. but you have to ask yourself — is it because you want to support the local economy or because you’re a racist?

i buy local produce. but nobody in my town makes high-quality bench planes. if i’m importing it from another city, i don’t worry too much how far away that city is or what language they speak there. neither should you. it’s always your choice, of course. but try not to be a racist. it doesn’t look good on anyone.

this is a personally-relevant issue for me. i design and make tools. i really enjoy it. some i just give away the designs of. others i actually hope someday to sell for a profit — i know, i know, i’m a communist and profit is evil but i live in a world where money is necessary for healthcare so i have no choice. if i design it and someone else copies it, that’s bad. i will complain. if i don’t design it but just build someone else’s design and someone else copies it… well, that’s fair. might not be fair to the person who copied it but it’s fair to me. if you’re curious, my current design project (and it’s been my tool design project for the last few years) is an adjustable metal benchplane that is designed to be comfortable when used as a pull-stroke plane. i am a japanese woodworker but the process of using a japanese plane is brutal and arcane so i use western planes on the pull-stroke instead. this is inconvenient and not as comfortable as it should be. but i digress.

back to vintage and new planes. if you’re going to buy a vintage plane, this can save you a huge amount of money if you can get one cheaply and in fairly good condition. if you like restoring old things and this is your hobby, that’s fine. but for most people you want something you can spend probably less than an afternoon getting in a usable condition. a good-quality new plane from wood river or quangsheng will cost you a couple of hundred bucks and a veritas will run you closer to three unless you get a great deal. so for a vintage stanley to be a worthwhile investment you have to remember two things — it’s not a very well-made piece of equipment and it’s old. this bears repeating. stanley mass-produced these things and their quality-control was abysmal. even the best examples of stanley engineering (before wwii, likely before wwi) are not even close to modern in terms of quality. i’ve seen far better produced in back-of-the-garage foundries. but that isn’t why you’re buying it and that’s not what made them great. they were mass-produced and inexpensive. and they’re absolutely good enough to get beautiful results. i have a few (ok, more than a few) and they’re brilliant. but they’re not modern tools and you can’t compare them in terms of price. my recommendation is simply this — if the stanley (or other old manufacturer like millers falls, record, etc) tool in reasonable condition costs more than about 25% of the cost of the new tool, it’s not worth it. i think this is a good benchmark. that means if a new wood river 4 costs $200, i’m willing to pay up to $50 for the vintage stanley. i’m not actually prepared to spend that much but i think it’s a good ballpark. in other words, spending a hundred bucks on a vintage 4 is a bit silly when you can get a far, far better new tool for $200 and absolutely no effort. it’s very much in the neighborhood of “if i can get a used car cheaply and it’s in good condition, it won’t be as nice as a new car but it’s a good idea — if i have to pay most of the price of a new car anyway, i might as well get that”.

here’s why this is relevant. the stanley 62 low-angle bevel-up jack is a mediocre plane. it’s not very well-made but it’s a brilliant piece of design. modern copies of it (like the one from wood river and that from lie nielsen) are excellent and work well. the stanley worked adequately. much like any old plane, it will take some screwing with to make it do what you want but it can definitely be worth the effort. here’s the problem. stanley made literally millions of 4s and 5s. they made far, far fewer 62s. and the 62s are popular now, despite not being popular when they were actually being made in the first place. high demand, low availability. that means they cost a fortune — in many cases not just more than 25% of the cost of the wood river copy (about two-hundred bucks) but more than the entire price of a new one — i’ve seen many of these sell for three-hundred or more in the last few years. this is beyond ridiculous. it was a poorly-made tool based on a very interesting new design. it’s what stanley did well — they designed something that was easy to manufacture and great to use then promptly mass-produced it with the expected quality level of the period, which was pathetic by modern standards. this isn’t a criticism of stanley. they did exactly the right thing and they were using excellent technology for the period while keeping costs low to make sure the average woodworker could actually afford the tools. the problem is the modern world has skewed this equation quite dramatically. if a vintage 62 that requires hours of work to get functional and was a comparatively-shittily-built piece of junk when it came out of the factory costs three-hundred dollars and a high-quality, precise modern version costs two-hundred, exactly how gullible do you have to be to get the 62?

there are other options, by the way, to get a low-angle jack in the modern world. the best one out there, hands-down, is the veritas and it’s about $250 (fluctuates a little but that’s a good estimate). this is the one you should buy if you want a good low-angle bevel-up plane. the wood river and quangsheng versions are generally a bit cheaper but they’re missing some of the modern refinements so i suggest getting the veritas at the slightly higher cost. don’t get a cheap one on amazon. you can get a grizzly or off-brand 4 or 5 and it will work just fine. low-angle bevel-up planes floating around on amazon are summarily excrement. if you’re thinking about getting one of those for your shooting board, just use your 4 or 5 and you’ll get better results with absolutely no additional cost. if you want to spend some money, get a veritas, wood river or quangsheng labuj (low-angle-bevel-up-jack) and you’ll be smiling all the way to perfect edges.

realistically, by the way, you can use just about any plane as a shooter. but you probably have a 4 or 5 or labuj (or want an excuse to buy one) and i don’t think there’s anything better for it. i’ve used my 6 and that’s good, too. it’s a bit heavy in the hand for the procedure but you get used to it very quickly and the extra mass is sometimes nice if you’re shooting something really dense like hard-maple or hickory. and in case you haven’t noticed from past articles, my goto woods are cherry and hard-maple.

what do i use? wood?

yes. you’re a woodworker. you can certainly make a shooting board from acrylic or metal. and that might be a good idea in some cases — actually, there’s no reason not to make a good portion of it from acrylic in just about every case. but there’s no need. you can use wood. there are a few caveats, though.

you can use any wood you like. it will work. but some woods are better than others for it and here’s why.

the whole structure is going to be subjected to a fairly high number of repetitions of racking, torsional impact pressure. wood that is highly-compressive or structurally-weak is a poor choice. what does this practically mean? use a hardwood. no pine, no fir, no spruce. yes, it’ll work. but you’ll find it simply won’t last nearly as long and this is a tool you can keep for decades if you build it well. it’s not a disposable thing you’re going to need to replace all the time unless you beat it up and don’t take care of it.

wood movement is a thing. we all know this. but in the case of something like this it’s extremely important to remember it. you can build this thing from maple or oak and it will need to be adjusted a lot more than if you build it from plywood. want it to look beautiful? hardwood. want it to be more efficient? plywood. good quality plywood. you don’t want any voids. that cheapass stuff from the box store? no. just don’t do that to yourself. for the tiny amount you’ll need for this, get something flat with lots of laminations. names for this kind of plywood vary by location but you’ll know it when you see it. there’s nothing wrong with using glued-up panels of hardwood, though. the wood movement isn’t that severe and you’ll be adjusting the thing anyway so it’s not a big sacrifice in effectiveness. in the end it’s up to you.

species that are good for shooting boards include maple, oak, hickory, ash, beech and even poplar (though it’s a bit light and flexible for the purpose — if it’s what you have, though, go for it). species that make awful shooting boards include pine, fir, spruce, basswood. if you want to use an exotic hardwood, that’s fine. it might be a little harder on your tools but the extra density and weight are a positive and there’s no downside. no need to get anything that expensive, though, for a shop project unless you happen to have some scraps and want to use them up — i can think of some better uses for beautiful exotic wood, though, like making accents in furniture or a few small decorative boxes.

let’s build a shooting-board

there are a few basic components of a simple shooting board and we’re making a simple one. you want a flat board as the base. you need another piece to sit on it to hold the fence and your board. there should be a cleat on the bottom so you can either attach it with a vise or a clamp to your bench — get in a rhythm with your shooting-board and you’ll have that thing flying off the end of the bench in no time if it’s not firmly secured. that’s it. it really is this easy. all that preamble and it’s just four pieces of wood? yes. but the magic is in how you attach them together.

let’s look at a few dimensions first. i’ll put this in a downloadable image shortly (if it isn’t showing up, let me know but it might be a couple of days before i can get around to it — writing is my life but making diagrams is a little less so). but this should get you the idea if you understand the basics of shooting boards. these are my recommendations for sizes and materials. you can vary them as needed for your desired results but this is what i use.

- lower base = 400mm x 450mm x 13mm (plywood)

- upper base = 400mm x 375mm x 13mm (plywood)

- cleat = 450mm x 30mm x at least 19mm but probably no more than 50mm (plywood or hardwood)

- fence = 25mm x 375mm x 25mm or slightly thicker (hardwood)

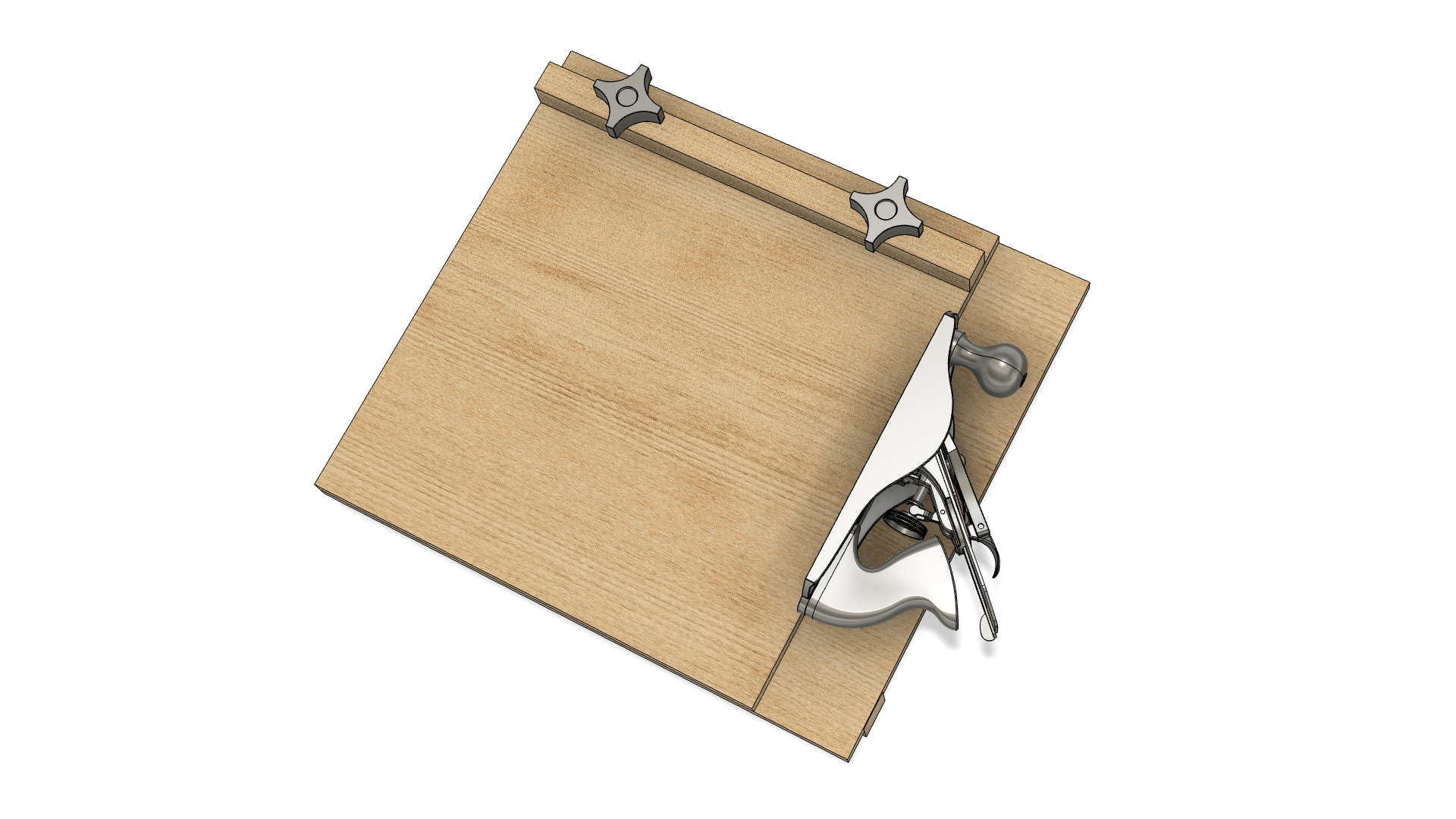

there are two ways of thinking about attaching that fence. either make it accurate or make it adjustable. accurate is a fool’s errand. even if you get it there today (which i suspect you won’t), it will be inaccurate when the moisture in your shop changes. jigs that aren’t adjustable are single-use, single-day, single-purpose. you want this to last years. make the fence adjustable. how to do that is up to you. but this is how i do it. route a groove in the upper base along the center-line of the fence and drop in a small segment of t-track. you’ll need a piece of t-track (if you are using my shooting-board dimensions) 325mm long. i use 17mm x 10mm t-track (17mm wide, 10mm deep) and it takes an m8 bolt. if you route the groove 25mm from the both edges of the upper base, 25mm from the top (far) side that’s 10mm deep and 17mm wide, that should do it.

once you have that done, drill two holes in the fence, each 40mm from an end and centered by thickness (yes, i’ll put it in the diagram). you can then drop two t-track bolts in the track, attach the track to the upper base, put the fence on top with the bolts sticking through the holes and attach two star-knobs on top. using your square of choice (i recommend a starrett 150mm adjustable combination square if you just want to have one in your shop but realistically you’ll end up with a collection of squares and just have to use anything you’re certain is square), lock the fence at exactly 90-degrees to the edge of the board and you’re going to get the desired results.

to assemble the rest of the shooting-board, it’s done pretty-much how you’d expect.

- flatten and surface all your pieces precisely to size. ensure parallel and perpendicular lines are accurate. this is a guide. any tiny error here will have disastrous results because it will be multiplied and duplicated across every part you cut with it.

- attach the upper base to the lower base with glue. wood glue is fine. clamp it and leave it to dry — this will take however long glue normally takes in your shop but leaving it overnight is probably sufficient for all purposes. the upper base should be flush with the left side of the lower base, leaving a 75mm lower platform on the lower base where your plane will ride. if your plane is small, you can always trim this platform narrower. it might get in the way of your hand. it might not. this depends on your plane and be prepared to rip a strip off this piece if you need to later. it doesn’t change the function of the shooting-board and it’s far easier to remove material than add it.

- cut a through-channel in your lower base at the near side 25mm from the end 50mm wide and 8mm deep. glue your cleat in this channel.

- insert your adjustable t-track fence system as described in the previous section.

- you can optionally route a channel at the left edge of the upper base to accommodate a speed-square but i don’t bother as my 45-degree square sits flush on the upper base.

the first time you use this, your plane will cut a small segment from the edge of the upper base and shoot the fence flush with the platform. make sure you have installed the fence slightly proud of the edge of the platform before starting so you can shoot it and have a zero-clearance backer for your wood. when the end gets worn, just shoot it flush again. you have an adjustable fence and this is a good portion of the reason why. the reason we’re not gluing it in is that this is the part of the board that will gradually get damaged. you can always replace it.

you may want to put some paste-wax on the platform to make the plane ride more easily back and forth. don’t wax the rest of the board or it will be harder to get wood to stay flat against the fence. if you want to finish it, use shellac. you don’t have to finish it at all and i generally don’t. it’s a shop fixture and you’ll keep it in a drawer or cupboard in your shop when it’s not in use. it won’t be beautiful but it’ll work. it’s not the fanciest shooting board ever — it doesn’t have to be. it just took you an hour to make it and it’ll shoot thousands of edges no problem. sounds good to me.

upgrades?

there are lots of bells, whistles and addons you can do with a shooting board. there’s only one i recommend. get a good 45-degree guide block you can clamp to the fence. if it has a ridge on one end, you can rip a groove the length of your upper base to accommodate it. mine sits flush with the top of the upper base so this is unnecessary for me. it will be better if it is missing the last 25mm or so of the corner on the side closest to your plane because you don’t want to get it in the way. if it’s a complete 45/45/90 triangle, just chop 25mm off one of the 45s. many commercial 45 guides already come this way. it doesn’t have to be expensive (read starrett). it just needs to be accurate. to check a 45-degree guide, put it against the edge of a surface then draw a line at 45. flip it and draw another line from the same point. take your 90-degree square and check to make sure there’s no compounded error in the resulting right-angle you’ve drawn. to check your square, do the same thing (almost). put it flush against the side of a straight board and draw a line, flip it, draw another line right next to the first. the two shouldn’t either approach or diverge their entire lengths. if they are parallel, your square is good. if your flipped 45-degree-guide can draw a right-angle, it’s good. put that against your fence, clamp it down, rest your board against that instead of the fence and you’ve got a 45-degree shooting board.

you can make a shooting board that adjusts to cut miters on the edges of boards as well as their ends and this is definitely possible to integrate. but you’ll end up with a painfully-complex single tool when what you’d probably have been happier with is two tools, each simple and able to do their jobs well. if this is a jig you’re interested in building, let me know. i don’t know if it’s really something people do enough of to warrant detailing its construction but i’m happy to if there’s interest. i use mine quite a lot for making small boxes.

to shoot other angles, all you need is a different guide clamped to your fence. there are adjustable miter guides you can buy that can replace the fence completely. veritas sells one that’s very accurate. before you do this, though, ask yourself one question — how often do you actually cut angles other than 90 and 45? not tapers. actual end-of-board angles. if the answer is “all the time”, get an angle guide. if the answer is anything else, just make a few guide blocks for the angles you need and keep them in a drawer — save the money. like most things, a tool you use all the time is worth spending serious cash on. a tool you rarely use is generally worth little.

aw, shoot!

i think that’s everything. of course, with such an involved description of a simple process, i’ve likely confused a few people along the way and raised more questions than answers for others. i hope this is helpful. if you have questions, though, please reach out either by email or on social media. have a different design for a shooting-board you like? build that. don’t like mine? don’t build it. i won’t feel insulted. i won’t debate the merits of one design or another and i’m not looking for improvements or suggestions. but i am here to help if you are looking for assistance. anyway, enjoy your shop time and thanks for reading! (if the diagrams aren’t showing here and the article was only just published this week, they’re probably not done yet — otherwise, they should be here and if you can’t see them you can always just ask for the files and i’ll email them.)